Jörg Hundertpfund spends a lot of time thinking about what designers do—and not only since Greta Thunberg. The ongoing effort around the world and how we use things to make it a better one is a central question for the renowned product designer and professor. Read his interview here.

Jörg Hundertpfund, product design professor and freelance designer

Mr Hundertpfund, you are a product designer and also teach young people design. Is it still possible to do that with a good conscience—given that following Greta Thunberg and Fridays for Future, sustainability is the watchword?

Jörg Hundertpfund: In our world, things define identity and for that reason, play a large role. The exploitation of resources, however, has created a new situation for us—which may be beyond the point of no return. It presents us with huge problems. Every step forward is an experiment with an unknown and possibly precarious result.

For many, it’s becoming too much. Perhaps that is why a young Japanese author recently caused a stir by explaining how to get rid of excess things: Marie Kondo’s guide to tidying up and clearing out has been translated into many languages and become a bestseller. “To kondo” has even become a verb to describe getting rid of unneeded things.

J.H.: That makes perfect sense: You could see consumers today as swimmers in a current—always striving to stretch their arms forward, pull things towards them, and then push those things away behind them again.

But these things pile up behind them and can no longer be pushed away, that’s when they have a problem; you become a horder against your will.

This could also be seen as a form of consumption: traveling

Then you need to find some advice.

J.H.: Yes, something that will tell you how to stop things sticking with you in the first place. How to swim through the mess of life. Perhaps we all just need to take up window shopping again. Or just borrow what we need. Acquiring possessions that have been mass-produced comes at the cost of human and natural resources. This is all very connected to possession and at the same time, a clear problem that we can no longer avoid.

Window shopping, borrowing, and sharing: A look toward the future shows that new habits would be useful.

But not buying things any more—is that the solution?

J.H.: We need to “earn” something before we can own it. And I don’t just mean that in terms of financial cost, but also earning in the sense of responsibility.

It’s always said that ownership is a responsibility…

J.H.: Yes. We do have a responsibility towards every thing that we own. Even if it’s just a paperclip.

And usually we own more than a paperclip.

J.H.: The average European owns around 10,000 things! And we have to deal with it all, take care of every single thing, and be responsible for it. In my opinion, that’s not something that’s being learned.

But can things also help us to be successful in life?

J.H.: Yes. We simply need to engage more with the things that surround us. That would not lead to mass consumption. I believe we would realize at some point that new things are not useful at all, unless you have the time to use them. Simply consuming things doesn’t help—at best, it brings us momentary contentment, which quickly becomes stale and feeds the drive towards the next purchase.

Hungry for the next consumer purchase? Perhaps sketching will take your mind off it.

You’re a designer. Aren’t making new products also commissions, jobs, and a part of what you do?

J.H.: Of course. In the business of design, every new job and product takes us further. They are our livelihood. But I have been saying for a long time that we cannot simply keep producing things… we need to react. And as a society, we need to reflect on what defines us.

What do you mean by that?

J.H.: When what I own is more important than the social, economic, or ecological environment in which I live, then this is a reality that we need to deal with somehow.

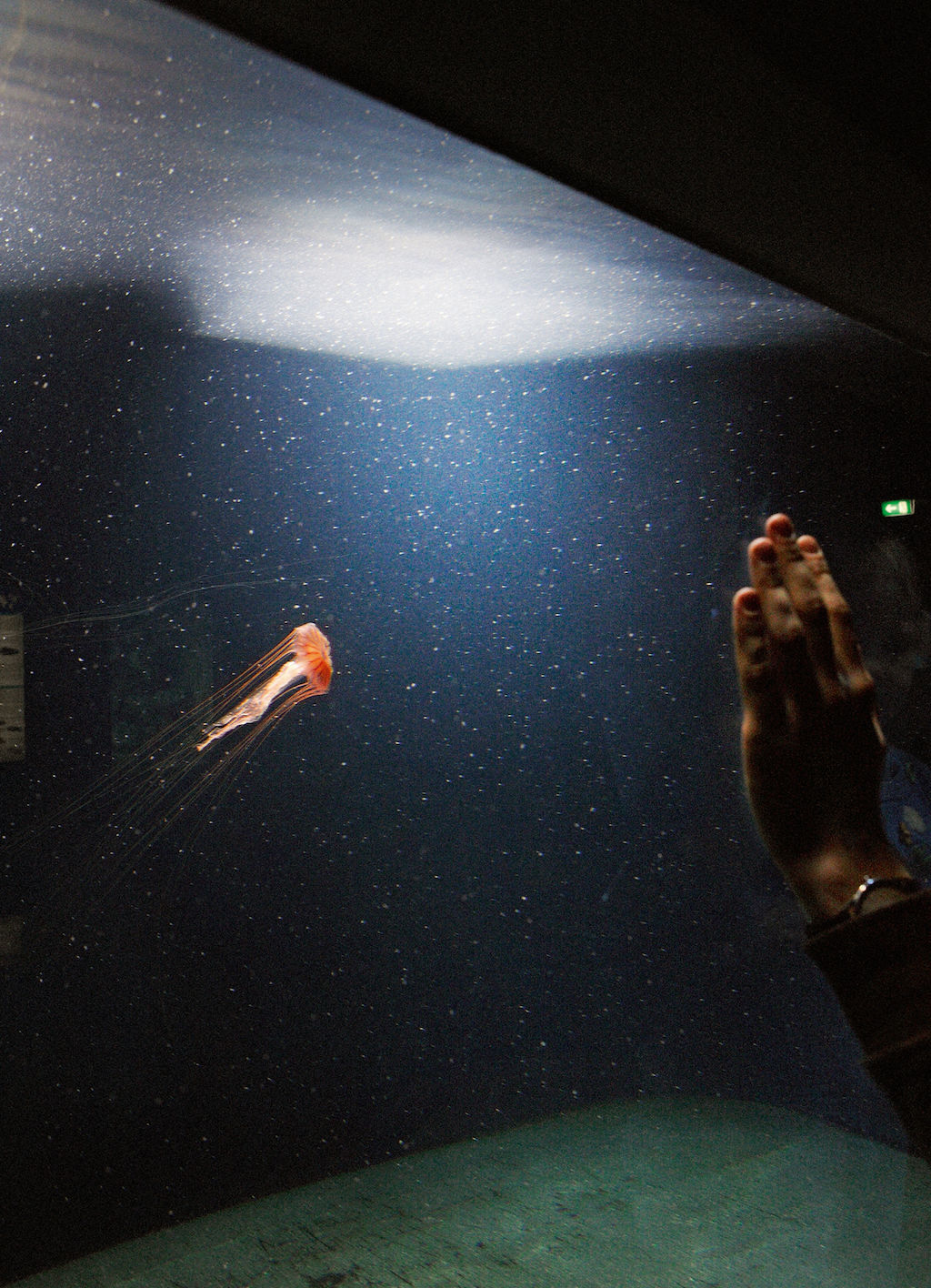

Jellyfish die and can then come back to life. As humans, it’s better to ask ourselves: What are the consequences of my actions?

Are there any good sides to consumption?

J.H.: Well, for example, we are highly mobile. That is a good thing—it educates and connects us. But we have to address the question of how we use this mobility. After all, no-one gets into a plane and asks themselves whether they will be welcome where they are going. The question is always: What is the consequence of my action? What does it have to do with me and to what extent does it affect other people?

And what do you suggest?

J.H.: Today everything has to be easily accessible, work straight away, be self-explanatory, and so on. I think that we should start to see things as a challenge and, in this sense, as an obstacle again. Then you have to spend some time with the things that surround us, thinking about the way we live and why we buy what we do.

Is that how something becomes a good thing to have?

J.H.: Yes, if you don’t just blindly grab things—which is something easier said than done. When the history can continue to be written, and when there is the potential for development in things. That is when another thing can be helpful and create a new, meaningful approach.

And is it sometimes worth buying a watch?

J.H.: Of course! Those who never have enough time could really use a watch.

PUBLICATION DATE: January 2020

TEXT: NOMOS Glashütte

IMAGES: NOMOS Glashütte/Benjakon