Stefan Sagmeister lives and works in New York. Although he recently caused a stir in Europe with major exhibitions in Frankfurt and Vienna on subjects such as happiness and beauty. Sagmeister explains here how beauty can make us better people: “Ideally we should be moved to tears.”

Mr. Sagmeister, we’re Skyping between Berlin and New York, but we still can’t see each other. Perhaps one of us is in PJs—after all, it’s still early in New York. Or am I wrong?

Stefan Sagmeister: I’m already dressed and ready for the day! In a blue suit and flowery blue shirt. Later I’ll throw on a blue patterned coat, pick up a friend who is a designer, and drive to Queens with her on my blue Vespa.

Blue’s a popular color.

S.S.: Definitely! On that, scientific research overlaps with my own. The majority of people always choose blue.

Why is that?

S.S.: People have always seen a blue sky as a safe sky. It means that there’s no storm. And a blue sea is a safe sea too.

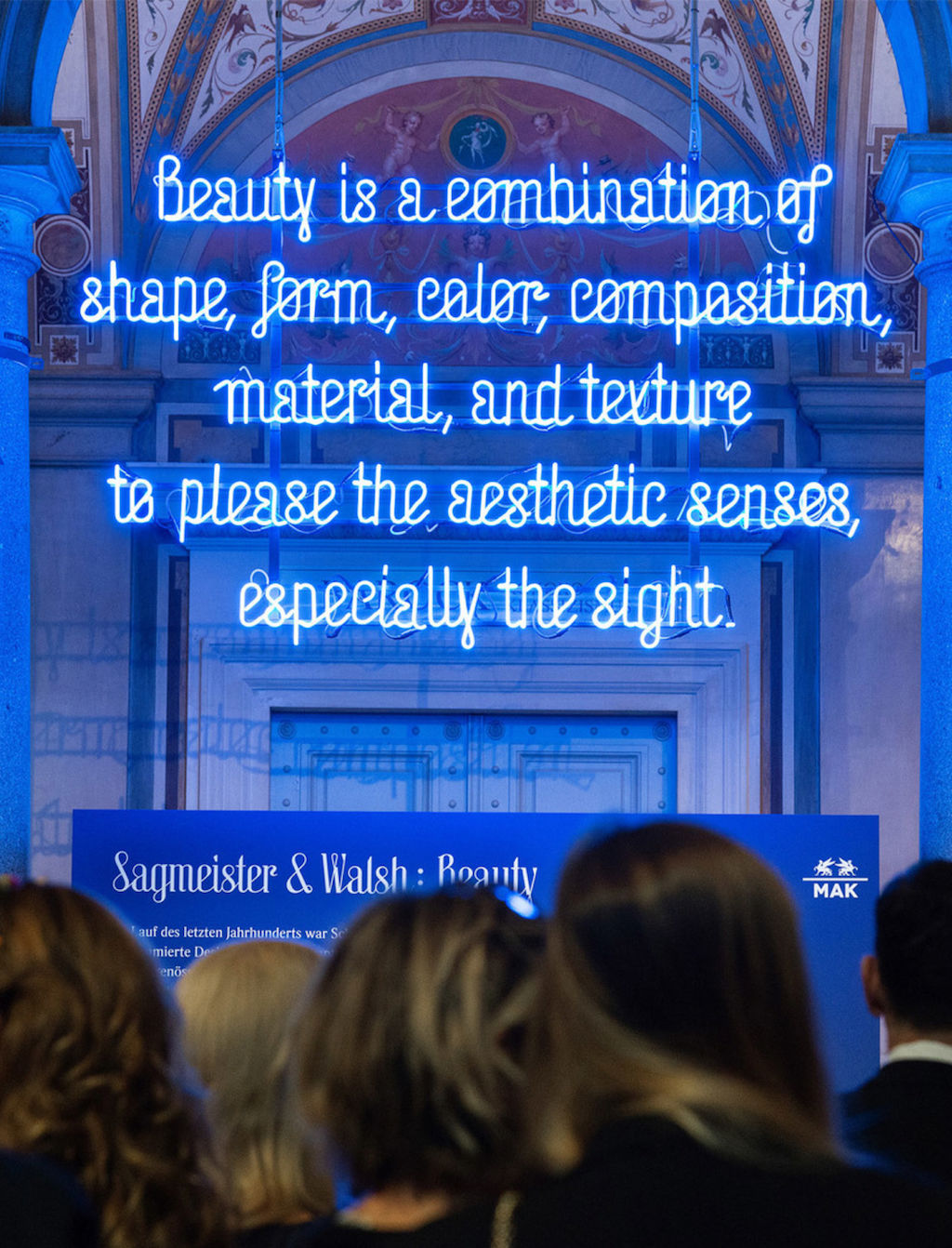

The Beauty project by Sagmeister & Walsh: A combination of form, color, composition, and materials.

That’s a great explanation! The title of your most recent project, which you created with Jessica Walsh, is “Beauty.” The subtitle is beauty equals function equals truth. Could you take us through that equation?

S.S.: Of course. In the era when functionalism was the dominant force—I would say from 1950 to 2000—many things that were technically built or produced under the guise of functionalism didn’t work properly. Such as the housing blocks of the 1970s that needed to be demolished back in the 1990s.

They weren’t beautiful enough?

S.S.: If the aim of these housing blocks was to be beautiful, as well as functional, then they would still be around today—and people would be happy to live in them. That means that they would be more functional too.

In the 20th and 21st centuries, beauty fell into disrepute. The belief was that beauty got in the way of the Enlightenment.

S.S.: Yes, I see it that way too. It was a terrible development, which we are currently in the process of correcting. I am convinced that we will view the second half of the 20th century very critically in 20 years’ time.

Max Bill, for example, was an early advocate for us to give beauty the same importance as functionality.

A desk with a view: Stefan Sagmeister’s desk and office in New York

And the principle of “form follows function?” Is that not true?

S.S.: The myth that something is good just because it works simply isn’t true. This interpretation of the statement “form follows function” by the architect Louis Sullivan is wrong. He meant something else entirely! Things have to do more than just be functional. Otherwise we view it as cold and, ultimately, as inhuman. In principle, beauty is about whether something is designed with love—or with indifference. 99 percent of what is ugly in the world is so because whoever made it simply didn’t care. Perhaps we could replace the term “beauty” with “intentionally-created form.”

Then this is the perfect moment to ask: Which of our watches is the most beautiful?

S.S.: Now I’m a big fan of watches in general. But I have a square blue NOMOS timepiece, Tetra neomatik.

Apparently, people like circles more than squares and rectangles—as you showed in your exhibition in Frankfurt.

S.S.: It is generally true that round things are considered more attractive than angular things; nature, after all, rarely produces sharp edges. So most things found in nature are rounded. Take indigenous architecture: Whether we look at Alaskan igloos, Native American tipis, or the Adobe houses found in the American Southwest and Mexico, there are many round details. Round things are safer, since we can’t hurt ourselves on them. Around the world, round things are more popular than angular ones. But I’m certainly not advocating that we only start to create circles from now on.

Beautiful gloves with a beautiful message: “Everything I do comes back to me.”

You also say that beauty can make us better people. Does that mean that beauty is a kind of finishing school?

S.S.: I think that being in beautiful places and around beautiful things makes us feel better—and behave better. If I go back to the 70s housing blocks as an example: In many places around the world, these were torn down not only because the people living there were unhappy, but also because they were behaving badly. Rates of criminality rose, everything was squalid, and men were urinating in every corner. People just don’t care about places like that.

Is there an equivalent in the online world?

S.S.: Of course. If you take the most functional of the major social media platforms—which is clearly Twitter—you’ll see that this is where people are the most aggressive to each other. All the Twitterstorms and cyberbullying have something to do with its strict functionality. On Instagram, by contrast, aesthetics plays a much larger role—and aggression is rarely a problem. And Instagram is growing ten times as quickly as Twitter. I assume that a watch from NOMOS Glashütte, which is extremely beautiful, also sells a lot better than other ones from another brand that are not as attractive.

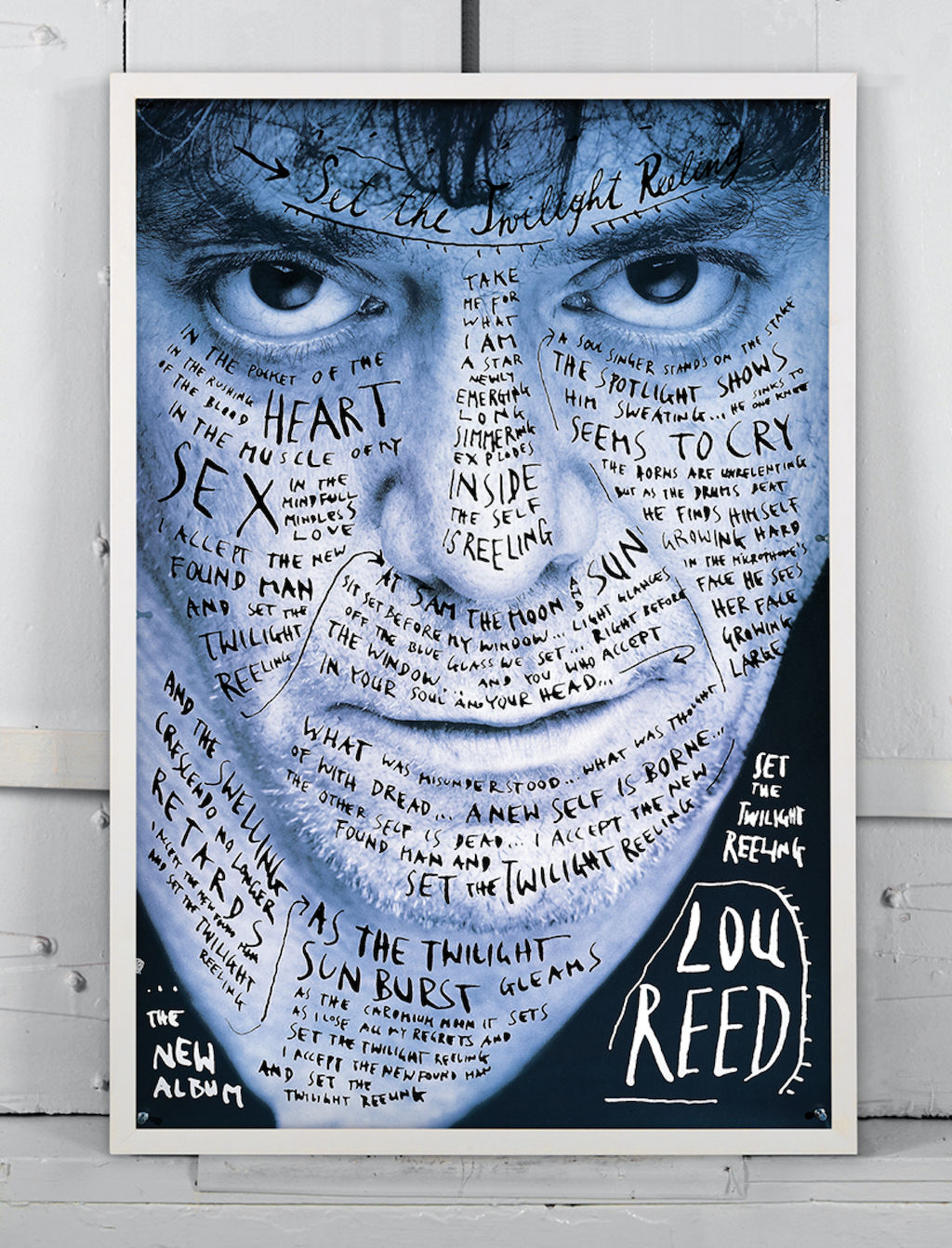

A commission—and a form of beauty: Writing on skin, Lou Reed’s lyrics on Lou Reed

If beauty teaches us manners: Can a good pair of shoes or a beautiful watch help us become better people?

S.S.: That might be taking a little far, but yes: Things like that help. The watch or the socks or the shoes that you choose definitely make an impact on our overall environment. And the watch has a bigger role to play than a pair of socks, since I’m looking at it more often.

What is your goal with your design? What does it have to do?

S.S.: It has to help people and delight them too! When I make things that are useful and a pleasure to use, then I’ve done my job right. There has to be a reason for this object to exist in the world. In an ideal world, the customer is more intelligent than we are—which means that we can learn something from them. We like it when our customers are nice people. Otherwise you might as well stay in bed.

How did it start with you and design—was there a defining moment?

S.S.: Our family always drove to a very simple house in Montafon, a valley in the Vorarlberg region in western Austria, and spent the whole summer with an aunt there. There was a small chapel near this house. In it, there was an image of an avalanche coming down the side of a mountain. Underneath there was a pious family on one side and, on the other, a group of people celebrating—who were buried by the avalanche.

So the pious ones survived, but the partygoers didn’t?

S.S.: Of course—the people busy partying were buried by the avalanche. It made an incredible impression on me. Naturally, I’m scared of avalanches. I’ve got a copy of that image, which now hangs in my bedroom here in New York.

Beautiful as well, and not only because it’s blue: The watch that Stefan Sagmeister wears, Tetra neomatik 39 midnight blue.

Stefan Sagmeister runs the eponymously-named studio in New York. In collaboration with Jessica Walsh, he recently held major exhibitions in Europe on subjects such as happiness and beauty. Sagmeister also teaches the graduate program at the School of Visual Arts and tries “to teach the students there a few things—including that the things we make must and should be able to function. And the things that we make must and should be able to delight people too.” When it works, he is moved to tears as well.

PUBLICATION: January 2020

TEXT: NOMOS Glashütte

IMAGES: 1. James Braund, 2. Sarah Hopp, 3. & 4. Stefan Sagmeister, 5. Timothy Greenfield Sanders, 6. NOMOS Glashütte